Figure 1: Here I am wearing a mask and posing in Venice, Giudecca island. On the back ground is possible to see the San Marco square and the Santa Maria della Salute church.

Venice, March 2020. Responding to the COVID-19 outbreak, the Italian government had declared a state of emergency.

As one of the main preventive measures, all the non-essential services had been closed. People were not allowed to leave their homes more than once per day. One of the requirements to go out and be in a public space or for being “in the immediate presence of the others[1]” was to wear the mask.

I started to reflect on what was happening around me in order to cope the situation.

The masks, the movement restrictions, the uncertainty.

Figure 2: Here I am wearing a mask. A mask without an intervention. The pictures as taken at the beginning of the mandatory mask law.

Living in Venice for more than 5 years, wearing a mask/mask rituals was/were not alien to me. However, every time Carnival season came around, I had always had concerns regarding wearing a mask, as well as which mask to wear. The Carnival is a folklorist celebration where the masks are something that as soon I have to wear it automatically I do a sort of tracing back its symbolic and historical background. However, that approach happens to me not all regarding the carnival and the masks, but for many other cultural practices and its objects.

According to Lakoff and Johnson the practice of…could be explained by the fact that “the concepts that govern our thought are not just a matter of the intellect [ but ] the way we think, we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of metaphor.[2]”

So my relation to masks is guided by the metaphors that I associate the mask with.

Without an alternative, I have decided to do some interventions on the masks in order to be able to detach them from their metaphorical, historical, and symbolic meanings, that I had mentioned above.

Also, it is important to remind that “the way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe.[3]”

Inspired by these words and my own experiences, I came up with the idea of printing images of historical figures that I admire and then assembling them right in front of the mask.

My idea was to look for, my personal heroes, people who historically had decided to initiate and organize resistance against an oppressor or a condition of injustice.

The idea of resistance and the need for change came to my mind because at certain point the Covid-19 and the needs to adopting some restrictive measures had started to be described as a sort of war.

The other selection criteria were the fact that those heroes were supposed to be universally heroes who were able to create a transnational audience.

Consequently, I chose Martin Luther King, Rosa Luxemburg, Fidel Castro, and Nelson Mandela. I printed their portraits on paper and attached them onto the masks.

It is interesting that after my intervention it was not anymore the masks that were noticed but the content that it carries. Indeed, Barthes reminds us that the “myth deprives the object of which it speaks of all History.[4]”

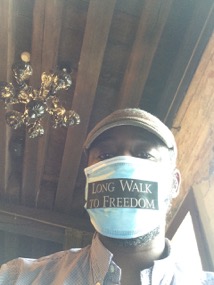

Figure 3: Here I am wearing a mask with the title of Nelson Mandela autobiography.

Before I had started to share the masks, I added two more masks. One with the title of the Nelson Mandela’s autobiography “Long Walk to Freedom[5]” and the second one with the symbol of the Black Lives Matter movement.

And the others had followed.

It was very interesting to see and read the comments that some of my friends made below the pictures of me wearing the masks.

After that, I got to understand that eventually what I was trying to do could be interpreted as not only a pretension to challenge the dominant discourses but also an intention to present my conception of Self.

As Erving Goffman reminds us ” When an individual enters the presence of others, they commonly seek to acquire information about him.[6]”

Indeed, at same time, the modified masks could be used as an medium to activate the identification or the different processes.

The identification, according to Stuart Hall ” is constructed on the back of a recognition of some common origin or shared characteristics [values, believes and ideas] with another person.[7]”

The artistic dimension of the project is not only acquired by considering the fact that the idea behind it was influenced by theoretical and practical reflections on art, but also by the fact that my practices or intervention on them had been guided by attempts and adjustment of these ideas.

It is interesting that the Covid-19 crisis response was also guided by the same modus operandi.

Figure 4: Hasta La victpria siempre. In my mask is missing “patria o muerte.” Was one of the Cuban revolution slogans.

[1] Goffman, 1956: 1.

[2] Lakoff & Johnson, 1980.

[3] Lakoff & Johnson, 1980: 103.

[4] Barthes, 2006: 100.

[5] See Mandela, N. (1995). Long walk to freedom: The autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Boston: Back Bay Books.

[6] Berger, 1972: 8.

[7] Hall, 2000: 16.

Works cited

Barthes, R. (2006). Myth Today. In M. Durham G. & D. M. Kellner (Eds.), Media and Cultural Studies Keyworks (pp. 100–106). Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

Danto, A. C. (1971). The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy, 61(19), 571–584.

Goffman, E. (1956). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. University of Edinburgh, Social Sciences Research Centre.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. The University of Chicago Press.

Mandela, N. (1995). Long walk to freedom: The autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Boston: Back Bay Books.

Marx, K. (1998). The Fetishism of the commodity. In Mirzoeff, The visual culture reader (Second edition, pp. 122–123). Routledge.